Indigenous Peoples and Early Exploration

Indigenous peoples inhabited the Americas for thousands of years before European arrival, with diverse cultures, languages, and traditions․ Native American populations were estimated in the millions, with thriving societies like the Aztec, Maya, and Inca in Mesoamerica, and tribes such as the Cherokee and Iroquois in North America․

1․1 Native American Cultures Before European Arrival

Native Americans developed sophisticated agricultural systems, trading networks, and governance structures․ Many lived in harmony with their environments, relying on hunting, gathering, and farming․ Their cultures were rich in oral traditions, spiritual beliefs, and artistic expressions․

1․2 European Exploration and Its Impact

European explorers, starting with the Vikings and later Christopher Columbus, arrived in the Americas, leading to profound changes․ This included the introduction of diseases, displacement of populations, and the beginning of colonial exploitation, reshaping indigenous life forever․

Before European arrival, Native American cultures were incredibly diverse, with over 1,000 distinct tribes across the continent․ Many societies were highly organized, with complex social structures, agricultural systems, and trade networks․ For example, the Aztec and Maya civilizations in Mesoamerica developed advanced calendars and architecture, while tribes like the Cherokee and Iroquois in North America established democratic governance systems․ Native Americans also had rich spiritual traditions, often emphasizing harmony with nature and ancestors․

European exploration of the Americas began in the late 15th century, led by figures like Christopher Columbus, who reached the Caribbean in 1492․ This marked the start of widespread European contact, leading to profound cultural, economic, and demographic changes․ Native populations were devastated by diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity․ European colonization introduced new technologies, crops, and animals, reshaping the environment․ However, it also led to exploitation, displacement, and violence against indigenous peoples, forever altering their way of life;

Colonial America

Colonial America began in the early 17th century with English settlements like Jamestown․ European powers established colonies for economic gain, religious freedom, and strategic purposes․ Settlers faced challenges, while Native Americans experienced displacement and cultural disruption, shaping the complex colonial era․

2․1 Reasons for Colonization

Colonization of America stemmed from economic, religious, and territorial ambitions․ European powers sought new resources and trade routes, while religious groups aimed for freedom․ Proprietary colonies were established for profit, such as the Virginia Company․ The desire to expand empires and spread Christianity also drove colonization․ These motivations laid the foundation for diverse colonial systems, shaping early American society․

2․2 Types of Colonies: Economic, Religious, and Proprietary

Economic colonies, like Virginia, focused on generating wealth through agriculture and trade․ Religious colonies, such as Massachusetts, were established for faith freedom․ Proprietary colonies, like Pennsylvania, were owned by individuals for profit and religious refuge․ These types shaped colonial life, economy, and governance, reflecting varied goals of European colonizers․

2․3 Daily Life in the Colonies

Daily life in the colonies varied by social class and location․ Wealthy elites enjoyed comforts, while most colonists worked as farmers or laborers․ Families focused on agriculture, trade, and survival․ Education and church activities were central to community life․ Women managed households, while men worked in fields or crafts․ Colonists faced challenges like disease, limited resources, and hard labor, shaping their resilience and adaptability in building new lives in America․

2․4 Relations with Native Americans

Relations between colonists and Native Americans were complex, marked by cooperation and conflict․ Initially, many tribes traded and allied with Europeans, sharing knowledge and resources․ However, disputes over land and cultural differences led to violence and displacement․ Native populations faced devastating impacts from diseases, marginalization, and forced relocation․ Over time, some tribes adapted to colonial presence, while others resisted, shaping the fraught history of early America․

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial revolt against British rule, leading to the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the birth of the United States․

3․1 Causes of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was sparked by growing colonial resentment toward British policies, including taxation without representation, the Proclamation of 1763, and restrictions on trade․ Enlightenment ideas about liberty and democracy inspired colonists to challenge British authority․ Additionally, the colonists’ desire for self-governance and resistance to imperial control fueled the rebellion․ These tensions escalated into protests, boycotts, and eventual armed conflict, culminating in the Declaration of Independence in 1776․

3․2 Key Events of the Revolution

The American Revolution began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, marking the first military engagements․ The Declaration of Independence in 1776 formally declared the colonies’ sovereignty․ The harsh winter at Valley Forge in 1777-78 tested colonial resolve․ The Battle of Saratoga in 1777 was a turning point, convincing France to ally with the colonies․ The Battle of Yorktown in 1781 ended the war, leading to the Treaty of Paris and British recognition of American independence in 1783․

3․3 Important Figures of the Revolution

Key figures of the American Revolution included George Washington, who led the Continental Army to victory․ Thomas Jefferson authored the Declaration of Independence, while Benjamin Franklin secured French support․ John Adams was a leading negotiator and politician․ Patrick Henry inspired patriotism with his “Give me liberty or give me death” speech․ Paul Revere and Samuel Adams were instrumental in organizing colonial resistance, ensuring their legacies endured as heroes of American independence․

3․4 The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, formally declared the 13 colonies’ independence from Britain․ Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, it emphasized Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and individual rights․ The document outlined the colonies’ grievances against King George III and asserted their sovereignty․ Its iconic phrase, “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” became a cornerstone of American identity, shaping the nation’s founding principles and inspiring future struggles for freedom and justice․

Early National Period

The early national period saw the establishment of the U․S․ government, shaped by the Constitution and Bill of Rights․ Challenges included national unity, economic growth, and territorial expansion, while the War of 1812 marked a defining moment in asserting American sovereignty and identity․

4․1 The Constitution and Bill of Rights

The Constitution, ratified in 1788, established the framework of the U․S․ government, creating a federal system with three branches and dividing powers between state and federal authorities․ The Bill of Rights, added in 1791, guaranteed fundamental liberties such as freedom of speech, religion, and the right to bear arms, ensuring individual protections under law․ These documents laid the foundation for American democracy, balancing authority and individual rights to foster unity and stability in the young nation․

4․2 Challenges of the Young Nation

The young American nation faced significant challenges, including establishing a stable government, resolving economic struggles, and managing regional divisions․ The Articles of Confederation proved inadequate, leading to the Constitutional Convention․ Economic hardships, such as debt from the Revolutionary War, required innovative solutions․ Additionally, the nation grappled with westward expansion, Native American relations, and balancing individual liberties with national unity․ These challenges tested the resilience and ingenuity of the new republic, shaping its future trajectory․

4․3 The War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the British Empire, driven by issues like British impressment of American sailors, trade restrictions, and support for Native American resistance․ The war saw key events such as the burning of Washington, D․C․, and the Battle of New Orleans․ It ended with the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, restoring pre-war borders․ The conflict fostered American nationalism and marked a turning point in U․S․ development, despite no significant territorial changes․

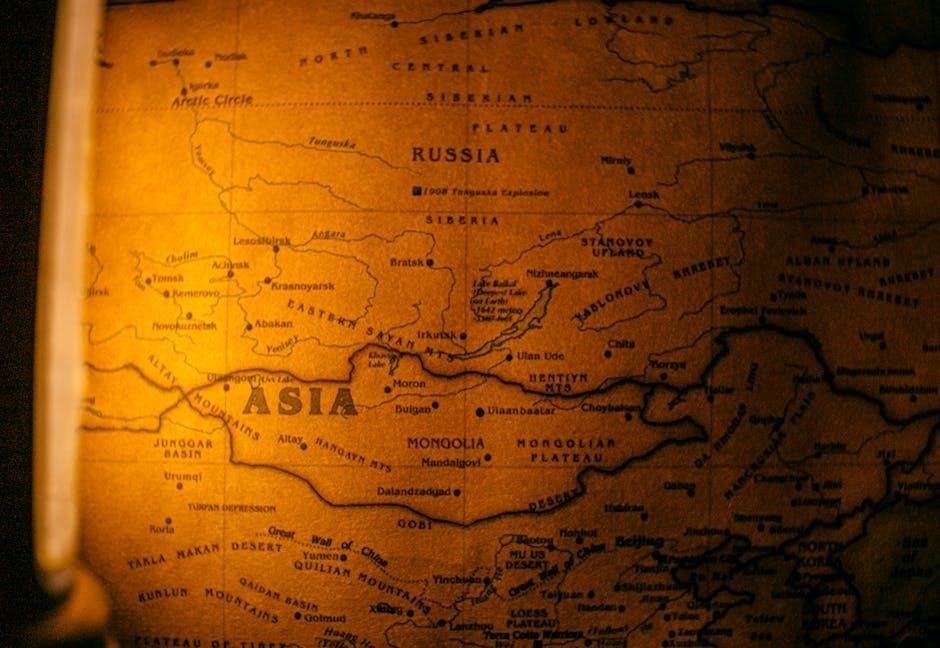

4․4 Westward Expansion

Westward expansion in the early 19th century was driven by the idea of Manifest Destiny, the belief that the U․S․ was destined to expand across North America․ The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 significantly enlarged U․S․ territory․ This expansion led to the displacement of Native American tribes, conflicts over land, and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, which connected the East and West coasts, fostering economic growth and further settlement․

Antebellum Period and Civil War

The Antebellum Period saw rising tensions over slavery, states’ rights, and economic differences between the North and South, culminating in the Civil War (1861–1865)․ The war resulted in the abolition of slavery and a more unified federal government, but at a great cost in lives and national division․

5․1 Slavery and the Underground Railroad

Slavery was a central institution in the antebellum South, with millions of enslaved Africans forced into labor on plantations․ The Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses, helped thousands escape to freedom in the North and Canada․ Harriet Tubman, a former slave, became a prominent “conductor,” guiding hundreds to liberty․ The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 intensified efforts to capture escaped slaves, but the Railroad persisted, symbolizing resistance against oppression and the fight for abolition․ Its significance endures as a testament to resilience and the quest for freedom․

5․2 The Debate Over States’ Rights

The debate over states’ rights centered on the balance of power between federal and state governments․ Southern states argued for greater autonomy to preserve their agrarian economy and institution of slavery, while the federal government sought to assert authority over issues like tariffs and western expansion․ The Mexican-American War intensified tensions, as new territories raised questions about slavery’s expansion․ The Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott decision further polarized the nation, highlighting the deepening divide that would eventually lead to the Civil War․

5․3 The American Civil War

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was a brutal conflict between the Union (Northern states) and the Confederacy (Southern states)․ Fought over slavery, states’ rights, and economic and cultural differences, the war began with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter․ Key battles like Gettysburg and Vicksburg turned the tide in favor of the Union․ President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (1863) declared freedom for enslaved people in Confederate states․ The war ended with Confederate surrender at Appomattox, leading to the abolition of slavery and a reunified nation, though at great cost in lives and lasting societal impact․

5․4 Reconstruction and the 13th Amendment

Following the Civil War, Reconstruction (1865–1877) aimed to reintegrate the South and establish rights for freed slaves․ The 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery nationwide․ The period saw significant challenges, including resistance from Southern states and groups like the Ku Klux Klan․ Legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Reconstruction Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th) sought to grant citizenship and voting rights to African American men․ However, Reconstruction’s promise was limited by the rise of Jim Crow laws and the Compromise of 1877, which ended federal enforcement of civil rights in the South․

Industrialization and Progressivism

Industrialization transformed America’s economy, fostering technological advancements and urban growth, while Progressivism sought to address social inequalities and reform practices through government intervention and public advocacy․

6․1 The Rise of Industrialization

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw rapid industrialization in America, driven by technological innovations, abundant natural resources, and a growing labor force․ Factories emerged, mass production began, and industries like steel, oil, and railroads dominated the economy․ Urbanization surged as workers moved to cities for jobs, leading to the growth of metropolises like Chicago and New York․ However, this period also brought challenges, including poor working conditions, long hours, and the rise of labor unions to address these issues․

6․2 Robber Barons and Their Impact

Robber barons, such as John D․ Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, dominated industries like oil, steel, and railroads during the Gilded Age․ Their business tactics often included monopolies, exploitation of workers, and ruthless competition․ While they revolutionized industries and amassed fortunes, their practices led to public backlash, labor strikes, and calls for reform․ Their influence shaped the economy but also highlighted the need for regulatory measures to balance industrial growth with social responsibility․

6․3 Immigration and Urbanization

Between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of immigrants arrived in the U․S․, driven by poverty and the promise of opportunity․ They came primarily from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as Asia, settling in cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco․ Urbanization surged as immigrants and rural Americans moved to cities for industrial jobs․ However, overcrowding, poor housing, and inadequate sanitation led to health challenges, such as cholera and typhoid outbreaks․ Despite these hardships, immigrants enriched American culture with their languages, traditions, and cuisines, shaping the nation’s identity․ Many faced discrimination and nativist movements, yet their contributions were vital to the country’s growth․

6․4 The Progressive Movement

The Progressive Movement, spanning the 1890s to the 1920s, sought to address social, economic, and political issues caused by industrialization and urbanization․ Reformers focused on improving workplace safety, promoting women’s suffrage, and combating corruption․ Muckrakers like Upton Sinclair exposed societal ills, while leaders like Theodore Roosevelt pushed for trust-busting and consumer protection․ While the movement achieved significant reforms, it struggled with racial inequality, often neglecting the rights of African Americans and immigrants․

World War I and the Roaring Twenties

World War I marked the U․S․ shift from neutrality to global involvement, while the 1920s brought cultural shifts, jazz, flappers, and consumer prosperity, defining modern America․

7․1 America’s Role in World War I

The United States initially maintained neutrality in World War I, focusing on economic gains through trade with both sides․ However, the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 and Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare shifted public opinion․ The Zimmermann Telegram, revealing Germany’s plan to ally with Mexico against the U․S;, further pushed America into the war in 1917․ U․S․ troops, including the American Expeditionary Forces, played a crucial role in turning the tide in favor of the Allies․ The war marked America’s emergence as a global power, though it also sparked domestic tensions and debates over international involvement․ The Treaty of Versailles and President Wilson’s advocacy for the League of Nations highlighted America’s new diplomatic influence, despite the Senate’s refusal to join the League․ The war’s aftermath shaped America’s identity and its role in global affairs, while also fueling isolationist sentiments that would persist in the decades to come․

7․2 The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance, spanning the 1920s and 1930s, was a cultural and intellectual movement centered in New York’s Harlem neighborhood․ It celebrated African American identity and creativity, producing iconic figures like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Duke Ellington․ This era saw a flourishing of literature, music, and art that challenged racial stereotypes and promoted pride in Black culture․ It remains a pivotal moment in American history, showcasing the resilience and richness of African American heritage․

7․3 Prohibition and the Jazz Age

Prohibition, enforced by the 18th Amendment, banned alcohol from 1920 to 1933, leading to widespread bootlegging and speakeasies․ This era, known as the Jazz Age, saw a cultural explosion of jazz music, flapper fashion, and shifting social norms․ Organized crime figures like Al Capone thrived, while the Harlem Renaissance flourished, blending music and art․ The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 marked a return to legal alcohol but left a lasting legacy of cultural and societal change in America․

The Great Depression and the New Deal

The Great Depression, lasting from 1929 to the late 1930s, caused severe economic hardship worldwide․ Franklin D․ Roosevelt’s New Deal introduced reforms and programs to stimulate recovery․

8․1 Causes and Effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression began with the 1929 stock market crash, triggered by overproduction, underconsumption, and reckless speculation․ Banks, heavily invested in the stock market, failed, leading to a credit crisis․

Unemployment soared, businesses shut down, and global trade collapsed․ Millions lost savings, and widespread poverty ensued․ The economic downturn lasted over a decade, deeply impacting society and prompting the need for drastic reforms like the New Deal․

8․2 Franklin D․ Roosevelt and the New Deal

Franklin D․ Roosevelt introduced the New Deal to address the Great Depression, focusing on relief, recovery, and reform․ Programs like the Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps provided jobs, while the Social Security Act established a safety net․ Roosevelt’s leadership restored hope and redefined the role of government in economic recovery, laying the foundation for long-term reforms․

8․3 The Lead-Up to World War II

The Great Depression weakened global stability, while aggressive powers like Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy pursued expansion․ The U․S․ initially maintained an isolationist stance, but events like Germany’s invasion of Poland, the fall of France, and Japan’s expansion in Asia heightened tensions․ America began supporting Allied nations through measures like the Lend-Lease Act and increased military preparedness, signaling a shift toward eventual involvement in the conflict․

World War II

World War II was a global conflict involving major powers․ The U․S․ entered after Pearl Harbor, contributing significantly to Allied victories in Europe and the Pacific․ The war concluded with atomic bombings, reshaping the world and positioning America as a superpower, while also laying the groundwork for the Cold War and domestic economic growth․

9․1 Major Battles and Turning Points

World War II saw pivotal battles that shifted the war’s momentum․ The Battle of Midway (1942) halted Japanese expansion in the Pacific, while the Battle of Stalingrad (1942-1943) marked a turning point against Nazi Germany․ The D-Day invasion of Normandy (1944) opened a western front, and the Battle of the Bulge (1944-1945) was Germany’s last major offensive․ These key conflicts, along with the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, led to Allied victory and the war’s conclusion․

9․2 The Home Front During WWII

During World War II, the U․S․ home front experienced significant changes․ Rationing of food, gasoline, and other resources became common to support the war effort․ Women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, particularly in industries like shipbuilding and aerospace, challenging traditional gender roles․ The war also spurred economic growth, pulling America out of the Great Depression, as industrial production soared․ Additionally, propaganda campaigns promoted patriotism and unity, while migration to cities near war industries accelerated social and cultural shifts․

The Cold War

The Cold War era was marked by ideological tensions between the U․S․ and Soviet Union, leading to proxy wars, espionage, and the Red Scare, which fueled McCarthyism․

10․1 Origins of the Cold War

The Cold War originated from ideological tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union after World War II․ The 1945 Yalta Conference and 1946 Potsdam Conference highlighted post-war divisions․ The U․S․ sought to spread capitalism, while the Soviet Union aimed to expand communism․ The Truman Doctrine and Marshall Plan symbolized American efforts to counter Soviet influence, while the Iron Curtain speech by Winston Churchill marked the symbolic beginning of the Cold War․

10․2 The Red Scare and McCarthyism

The Red Scare, fueled by fears of communism, emerged in the U․S․ during the late 1940s and 1950s․ McCarthyism, led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, involved accusations of communist infiltration without evidence․ This period saw blacklists, public hearings, and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) targeting suspected communists․ The era stifled free speech, damaged reputations, and created widespread fear, significantly impacting Hollywood, academia, and government, while undermining civil liberties in the name of national security․

10;3 The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement sought to end racial segregation and discrimination in the U․S․, gaining momentum in the 1950s and 1960s․ Key events included the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the March on Washington, and the Selma to Montgomery Marches․ Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr․ advocated for nonviolent protest, while others, like Malcolm X, embraced more radical approaches․ The movement led to landmark legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, fostering equality and reshaping American society․

Modern America

Modern America encompasses key events of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including the 2008 financial crisis, the impact of 9/11, and contemporary issues like social inequality and technological advancement․

11․1 Key Events of the Late 20th Century

The late 20th century saw pivotal moments in American history, including the Civil Rights Movement, the moon landing in 1969, the Vietnam War’s end in 1975, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989․ The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the rise of the internet, the Gulf War, and significant social and cultural shifts․ These events shaped modern America’s political, technological, and social landscapes, setting the stage for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century․

11․2 The Impact of 9/11

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks profoundly impacted America․ Nearly 3,000 people died in the World Trade Center, Pentagon, and Pennsylvania crashes․ This led to the War on Terror, creation of the Department of Homeland Security, and the Patriot Act․ It sparked wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, altering U․S․ foreign policy․ Domestically, there was a surge in Islamophobia and increased surveillance․ These events reshaped national security, civil liberties, and international relations, leaving a lasting legacy in American history․

11․3 The 2008 Financial Crisis

The 2008 Financial Crisis, triggered by the housing market collapse, led to massive job losses and home foreclosures․ Banks and financial institutions faced bankruptcy, prompting a $700 billion bailout․ The crisis caused a deep recession, affecting global markets․ President Obama’s stimulus package and reforms like Dodd-Frank aimed to stabilize the economy․ The crisis exposed systemic risks and reshaped financial regulations, leaving a lasting impact on America’s economic policies and recovery efforts․

11․4 Contemporary Issues in America

Modern America faces challenges like racial inequality, political polarization, and climate change․ Economic disparities persist, with wealth gaps and access to healthcare remaining contentious․ Immigration debates and technological advancements shape societal dynamics․ The rise of social media influences culture and politics, while issues like gun violence and education reform demand attention․ These complexities reflect America’s evolving identity and its ongoing struggle to balance unity and diversity in a rapidly changing global landscape․